|

According to membership records Thomas Morgan joined the Mormon Church in September 1851 and Ann in Feb. 1852, probably when

they were living in Bishops Frome. A decision to join with the Mormons was not one taken lightly. On one hand it was typically

met with some level of scorn or ostracism from friends and relatives and on the other hand it meant leaving home for a long

and arduous trip to the frontier of America. Poor families such as the Morgans could not make such a trip without the help

of the Mormon Church and perhaps others. So when it came time for Thomas to apply for passage on a ship to America, he made

his application to Mormon Church authorities in England. In February of 1855 he and his family were granted space on the

ship Siddons, chartered by the Church especially for Mormon emigrants. To help secure this passage he paid an initial small

deposit of £4/0/0 (four pounds no shillings, no pence) for "steerage" (third class) down in the lower deck of the

ship. This amount would have been equal to several days of work as a farm laborer in England at that time. He would owe

an additional £10/0/0 at some time in the future. He probably paid this debt in the form of labor after reaching Utah.

On Feb. 27, 1855, they boarded the Siddons in Liverpool, England, and set sail for Philadelphia, arriving there on 21

April 1855. All members of the family were listed except for their oldest son Edward. Edward had already emigrated to Utah

with his uncle Joseph Morgan in 1853. He and uncle Joe boarded the ship Elvira Owen in Liverpool on 15 February and arrived

in New Orleans March 31, 1853. They crossed the plains together, Edward being only nine at the time, in a wagon train led

by Jacob Secrist.

The wooden ship below, the "James Nesmith" is similar to the "Siddons" which brought Thomas and Ann Watkins

Morgan and their family to America.

The Ship "James Nesmith" Carried LDS Church Danish converts from Liverpool, England to America in 1855, the same

year the "Siddons" brought the Thomas Morgan family to America. The James Nesmith, a three masted wooden ship with

two decks, was built in 1850 at Thomaston, Maine, weighed 991 Tons and was 171 feet long. It left Liverpool 7 January 1855

and arrived at New Orleans 23 February, a forty seven day passage. There were 440 Scandinavian Saints onboard and the passenger

manifest listed thirteen deaths during the crossing.

The Siddons, which brought the Thomas Morgan family to America, was also a three masted, square rigged wooden sailing ship

like the James Nesmith, but, at 895 tons, it was smaller and, having been built in 1837, older, than the James Nesmith. The

Siddons left Liverpool 27 February 1855 and arrived in Philadelphia 21 April 1855, a voyage that took almost two months. There

were 430 LDS passengers on the Siddons.

Many of the 430 LDS passengers embarking on the Siddons were being assisted financially by the LDS Church fund called the

Perpetual Emigration Fund. Poor members who qualified for emigration under the auspices of the P.E.F. borrowed from that

fund and were to pay back into the fund over a period of time after they arrived in Utah. Payment could be with money or in

the form of labor on various church-sponsored projects. P.E.F. emigrants were formed into P.E.F. companies so that the church

could more easily charter ships and riverboats and acquire supplies for wagon trains for each of such groups.

Thomas Morgan and his family traveled with a P.E.F. group when they boarded the ship. The Church kept careful records

of all member emigrants who traveled in LDS-sponsored groups, especially where P.E.F. funds were used to charter ships or

aid in the emigration process. Although the Morgans were listed in the Churchs Siddons departure log as "ordinary"

passengers rather than as P.E.F.-sponsored, they traveled with P.E.F. passengers all the way to Utah, and this helps us track

their route. Mormon Elder John S. Fullmer was put in charge of the 430 LDS members on the Siddons.

Many of the ships crossing the Atlantic in the 1850s were driven by steam engines rather than by sails. But sailing ships

were still used in the 1850s because they were cheaper than steamships. The Siddons was an old sail-driven ship built in 1837,

so on this voyage it struggled against westerly winds that slowed it down when plying the Atlantic to America. The Morgans'

cheaper "steerage" tickets were for the deck down below those of the second and first-class passengers. This was

not a comfortable cruise. On the voyage taken by the Morgans, it took the Siddons nearly two months to cross from Liverpool

to Philadelphia because of "contrary winds." U. S. Customs listed the Thomas Morgan family as passengers from the

Siddons who disembarked there and every family member, even baby Priscilla, declared two trunks of goods each.

The author, Conway Sonne, states that after a railway ride to Pittsburgh, "The Saints from the ship Siddons [in 1855]

took an unnamed steamboat from Pittsburgh to St. Louis, arriving there May 7.... The next day some of these emigrants continued

on [up the Missouri River] to Atchison, Kansas, on board the 297-ton side-wheeler [steamboat] Golden State... Other emigrants

from the ship Siddons boarded the steamboat Polar Star ... which left St. Louis early in May..." for a ride up the Missouri

River to Atchison, Kansas, where they disembarked.

It is about 600 miles in a straight line from Pittsburgh to St. Louis. But, of course, the rivers are not straight.

They meander considerably, making actual river distance from Pittsburgh to Atchison probably close to 1200 Miles. A little

more than four miles west of Atchison, the emigrants from the Siddons gathered early in the summer with many other Mormons

in the outfitting point known as Mormon Grove, Kansas.

The LDS Church official who founded Mormon Grove was Milo Andrus, the leader (Stake President) of all Mormons in the St.

Louis area. During the summer of 1855 he directed thousands of Mormon emigrants to Mormon Grove where he could organize them

into several wagon train companies, purchase cattle, oxen, and other supplies needed to get them started on their way to the

Salt Lake Valley. The Morgan family remained in Mormon Grove until the very last wagon train to leave there that season.

They possibly worked on the farm at Mormon Grove which was growing potatoes and vegetables for the emigrants. That last

train departed Mormon Grove on August 5. It was led by Milo Andrus. The Milo Andrus wagon train company was identified in

migration records as a P.E F. company consisting of 452 persons. It arrived in Salt Lake on October 24, 1855.

Few words were ever recorded by anybody about this particular wagon trip across the plains. Our Morgan families wrote

not a word of their adventures on the seas or across the plains. Their leader Milo Andrus wrote a letter to his friend when

the train had crossed the Big Blue River in Kansas on Aug. 15, and again 30 miles up the Little Blue River in Nebraska on

August 22. He wrote a third letter when his wagons were 12 miles east of Fort Laramie, Wyoming, on the Platte River on September

13. In these letters Elder Andrus says almost nothing about the journey itself except for a few casual references to a few

people who got sick and that very few had died, and on the whole everyone was generally in good health and good enough spirits

to sing in the evening.

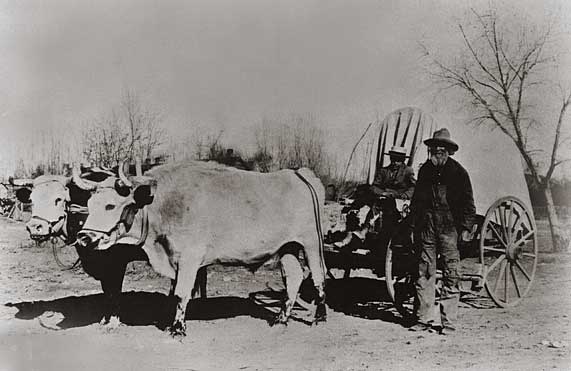

A Mormon wagon train crossing the plains

A group of Mormon Pioneers going about the hard and dirty job of getting to Utah in the 1850's

When his wagon train got to its destination in Salt Lake Valley on October 24, 1855, Thomas Morgan was listed in the roster

of this train. Three of the people who died on this journey were identified as William Davies, a child Elizabeth Davies,

and child John Davies. It is not known if these Davies, who bore the surname of Thomas' mother, were relatives of the Morgans.

Though nothing in particular is known about the Morgans' experience while crossing the nearly 1200 miles from eastern

Kansas to the Salt Lake Valley, we can extrapolate from historical sources and the diaries of others which illustrate typical

experiences and dangers.

All wagon trains could find their way along the route much easier if they followed designated rivers wherever possible.

Most Mormon wagon trains followed the established Mormon Trail, which left from Winter Quarters near present Omaha, Nebraska,

and followed the Platte River upstream along the north bank. The Platte flows eastward from central Wyoming to the Missouri

south of Omaha. Wagon trains leaving from Kansas, such as the one the Morgans were in, headed for the south side of the Platte

River, which they reached near present Hastings, Nebraska, by following up two rivers out of Kansas (Big Blue and Little Blue

Rivers). Though the Platte was not deep enough for riverboats (in fact it was very shallow in some places), it led to an

easy pass through mountains in Wyoming and it had necessary resources, such as water, better grazing grass, and woods in some

places.

Upon reaching Fort Laramie, which was on the south side of the Platte in eastern Wyoming, the wagon trains would stop

for provisions and a rest. Continuing westward, beyond present Casper, Wyoming, the emigrants headed for a broad open pass

more than 7,500 feet above sea level called South Pass, which is a "continental divide" that divides headwaters

of rivers. Eastward from the pass, rivers like the Platte flow east to the Missouri. West of the pass, rivers flow south

or west to the Pacific or the Great Salt Lake. Traveling through South Pass signifies that the emigrants, with relative ease,

had gone around some major mountain ranges of the Rockies. From South Pass the wagons headed toward Fort Bridger or Fort

Supply near present Evanston, Wyoming, where they again obtained provisions. The last leg of the journey was to traverse

Utahs Wasatch Mountains through present Echo Canyon and Parleys Canyon down into the Salt Lake Valley.

From the Journal of John William Dutson, a native of Herefordshire whose family crossed the plains in 1857, and who later

became neighbors to the Morgans while living in Millard County, Utah, we read [page 24]:

"The company got an early start and traveled without difficulty in the morning. The cattle were very quiet to all

appearances until they got to Rattlesnake Creek. Our cattle [then] became very restless. We moved on. Some Sioux Indians

came to us. They were friendly toward us. We got dinner and then moved on ... I have just been back and cautioned all in

my ten to rope their lead cattle that were wild. When I had just got to the second wagon ... of the ten, a team in the third

ten run, starting [startling] the whole train. At this moment I took a large club and prepared myself to do the best I could

to save the lives of the people. I yelled to the women and children to stay in their wagons and not to jump out. But many

of them jumped out while the wagons were coming in all directions. Many were run over and some were expected not to live.

I broke [stopped] the train [from stampeding] as well as I could with a club ... and thereby saved the lives of many that

was lying on the road that jumped from the wagons. Brother Terry and I ... administered [a prayerful healing blessing] to

them as we found them on the ground. Some of them would ask us to administer to them a number of times ... they began to

recover. There was a great many injured but no one was killed. We then carried those that were hurt ... to their wagons,

pitched their tents and stopped to attend to the wounded."

This quote illustrated many things about traveling in a Mormon wagon train during the Mormon migration, for example:

"getting an early start" in the morning. According to author H. H. Bancroft, migrants were awakened as early as

5:00 AM to begin breakfast and preparations for the days journey. In a large train it could take up to two hours to make such

preparations. Departure by daybreak would be a common goal. John Dutson mentioned "Rattlesnake Creek" which was

necessary to ferry across. Even though the Mormon Trail stayed mainly on the north bank of the Platte River, several tributary

streams enter the Platte from the north. Many of these streams were easy to cross but some were hazardous, time consuming

and dangerous.

The Milo Andrus company left from Kansas and likely traveled up the south bank of the Platte, the trail commonly traveled

by non-Mormon emigrants en route to Oregon. The south bank also has tributary streams that had to be crossed. Especially

big is the South Platte River which enters the main Platte near the present city of North Platte, Nebraska. Ester Stevenson,

who was in the same wagon train as the Dutsons, wrote in her diary [page 22] that:

"One difficulty we had to meet was fording the larger streams where there were no ferries. Always there was the

danger of quicksand. All who were able had to wade across, and many times we came out of the almost ice-cold water with our

clothes wet to our necks and had to walk on while the sun dried them. It was a terrible experience for those who were delicate,

and many times some were almost overcome in the stream. "

Adult men and older boys carried children and some women across the streams.

John Dutson also commented on being visited by friendly Sioux Indians. Indians were feared as they frequently visited

the Mormon trains. Indians typically approached a wagon train in small numbers and when they did they faced hundreds of armed

people in the wagon train, but there were usually no threats on either side. The Indians were usually curious and friendly,

sometimes wanting to trade for goods. Sometimes, during the night, Indians would attempt to stampede cattle in order to steal

them. But rarely was a Mormon traveler killed by Indians while crossing the plains. There were other dangers far worse than

the threat of Indian violence.

Anything that would stampede cattle was of great concern to the travelers as clearly indicated by John Dutson, for such

an event would wreck havoc on wagons and injure or kill people. Dutsons diary contains comments every day about the conditions

of the cattle being driven along as well as the oxen pulling the wagons. He was constantly concerned about whether the cattle

would get nervous and stampede. Johns references to "administering" to the injured refers to a well established

Mormon practice. Men with priesthood authority, while placing their hands on the head of the injured, said a prayer and blessing,

calling on the Lord to heal the person. We can imagine that many people asked for and received this rite while emigrating

to Salt Lake.

Brother Dutson also refers to "wagons of ten." This refers to the way the wagon train company was organized.

Dutson was a "Ten Captain." Each wagon train was led by a hierarchy of captains with one commander in charge of

the whole train. The commander would have subordinate captains for each unit of 100 wagons, each led by a Hundred Captain.

They were further divided into units of fifty wagons, each led by a Fifty Captain, with each of them divided into units of

ten wagons, each led by a Ten Captain.

Strict discipline and order were required by all captains. Alcoholic drinks and even swearing were forbidden. Disputes

between travelers were quickly settled or mollified. In contrast to often contentious relationships of migrants in non-Mormon

trains, Mormon migrants addressed one another as "brother" and "sister" or "elder." The well-being

of the whole and harmony were positively promoted as necessary tenets of their faith and for the success of the trip.

A Mormon wagon train entering the Salt Lake Valley

This Mormon wagon train is just emerging from Echo Canyon into the Salt Lake Valley. Note the tree branches laid across the

wet spot in the foreground to keep the wagons from sinking into the mud. These were called corduroy roads. Also note that

the front covered wagon, pulled by oxen, has a chair and a rocking chair for seats. The second wagon, pulled by mules, is

not a covered wagon and could have been a cargo wagon.

Dutson also refers to women and children as being in their wagons. Actually, whether people rode in wagons or walked varied

greatly from train to train. Beginning in 1856 companies without oxen pulled all their goods in wooden handcarts, walking

all the way. But even the ox-drawn wagon trains were often so heavily laden with provisions that there might not be enough

room in the wagons for the able-bodied to ride, except for the teamster. Riding in a wagon, none of which had springs, was

bumpy and jarring. Most people walked all the way, wearing their shoes out early on, some going barefoot most of the way.

Another problem with the wagons was that they frequently broke down. Milo Andrus mentioned in his letters that his company

had some problems with broken-down wagons which usually slowed the whole train down.

When camping for the night, the wagons were arranged end for end in a circle like a fort. Cattle were driven into the

corral and watched by assigned herdsmen. Campfires and all camp activities were outside the circle. Some slept in wagons,

others in tents. Buffalo chips or sage brush were common sources of fuel when there was no wood. After a dinner, hymns were

sung in the evening to bolster morale and foster a sense of community. At about 9 or 10:00 PM a bugler, when available, would

call taps for prayers and bedtime. Each night some men would take their turn at guard duty, a job which rotated in turn to

all able men and older boys. The day began typically at five AM. By seven AM they were on their way, hoping to travel from

10 to 20 miles, grazing livestock along the way.

Wagons were pulled mostly by oxen, though mules or more expensive horses were sometimes used. In addition there were

horsemen available to help control cattle, go on hunting excursions, or any needed quick maneuvering. Some wagons had small

hen coops attached to the back or a place for a few small pigs. Food provisions for the trip largely consisted of dry foods

such as wheat flour, bacon and ham. Some milk was drawn from a few cows. Game was hunted along the way but hunting for food

was unreliable.

A small wagon pulled by oxen

The people in this picture are not our Morgan ancestors, but they illustrate how our ancestors must have looked during the

wagon trip to Utah and probably much of the time. People did not have hot showers or electric razors in those days and woolen

pants or overalls were the most practical everyday clothes.

The first home in Utah for the Thomas and Ann Morgan family was in the town of Kaysville, located about 20 miles north of

Salt Lake City on a somewhat narrow strip of good farming land between the Great Salt Lake and the Wasatch Mountains. Thomas'

young son Edward and Thomas' brother Joseph, were already settled in Kaysville two years before Thomas and Ann's family arrived.

Thirteen year old son Edward must have been happy to see his family again. Kaysville was a frontier Mormon settlement founded

in 1850. After more than a year there, Thomas and Ann had their first Utah-born child: William Thomas, born in Kaysville,

26 December 1856.

Thomas' brother Joseph married Hannah Weaver in Kaysville in 1856 and they remained there the rest of their lives. She

was a native of Bishops Frome and a descendant of the Watkins family. Joseph died on 8 June 1886 in Kaysville. Hannah died

in 1916. He and Hannah had six children, all born in Kaysville.

Sources Used for Morgan Emigration

Arrington, Leonard Great Basin Kingdom An Economic History of the Latter Day Saints. 1958 University of Nebraska Press,

Lincoln. Explains Perpetual Emigration Fund.

Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, Mormon Emigration,

1963, "Our Pioneer Heritage," Vol. 6, page 262

Flack, Dore Dutson, et al. Dutson Family History Vol. 1, Revised.

1998. Privately published by the authors. Pages 19-29.

Kimball, Stanley B. Historic Sites and Markers Along the Mormon and Other Great Western Trails. 1988 University of

Chicago Press, Chicago. See Mormon Grove pages 130-131.

"Mormon Emigration Records from Liverpool," FHL Film #0025690

(1855 Siddons page 121 and 1853 Elvira Owen page 107.)

Journal History of the Church [Mormon] FHL Film #1259741. Events in Mormon history entered by date, contains the Milo

Andrus letters.

The "Milo Andrus Papers," University of Utah Special Collections Library, especially "The Recorder"

newsletter pages 60-73.

"Passengers Lists of Vessels Arriving at Philadelphia, 1855." FHL Film #419 652 (National Archives Roll #78).

Sonne, Conway B. Saints On The Sea A Maritime History of Mormon Migration. 1983 University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City,

pages 108-109.

Sonne, Conway G. Ships, Saints, And Mariners: A Maritime Encyclopedia of Mormon Migration 1987 University of Utah Press,

Salt Lake City, page 181 on the Siddons.

|